goldieseeker

tools for analyzing Goldie Seeking strategies in Splatoon 2's Salmon Run mode

Project maintained by redoxwarfare Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Optimizing Goldie Seeking for Fun and Profit(?)

in which we attempt to dissect a children’s video game using discrete math

This post is split into two parts. The first part attempts to explain the underlying mathematical concepts for those without any background, while the second part jumps straight into the mathematical detail.

Part 1: The Problem

You are trying to find the Goldie, which has randomly chosen one of several gushers to hide inside. You can open gushers to check if the Goldie is inside, but opening an incorrect gusher releases hordes of hostile fish. The gushers are also connected to each other by underground waterways. If an opened gusher is connected to the gusher hiding the Goldie, it will be high; otherwise, it will be low.

How can you find the Goldie as quickly as possible while releasing as few enemy fish as possible?

Diving a Little Deeper

Before we can properly attack this problem, we need to go over some of the mathematical objects we’ll use to describe it. We’ll represent the network of gushers using a structure called a graph, and we’ll represent the strategy for opening the gushers using a structure called a tree.

What Are Graphs?

A graph is a set of objects called vertices, some of which are connected to each other by edges. In Salmon Run, the set of gushers on the map form the vertices of a graph. If the game considers two gushers to be connected (adjacent) to each other, we draw an edge between the corresponding vertices.

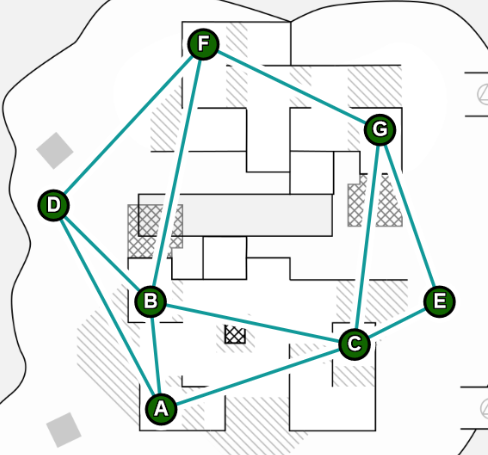

This is a graph of the gushers on Salmonid Smokeyard:

What Are Trees?

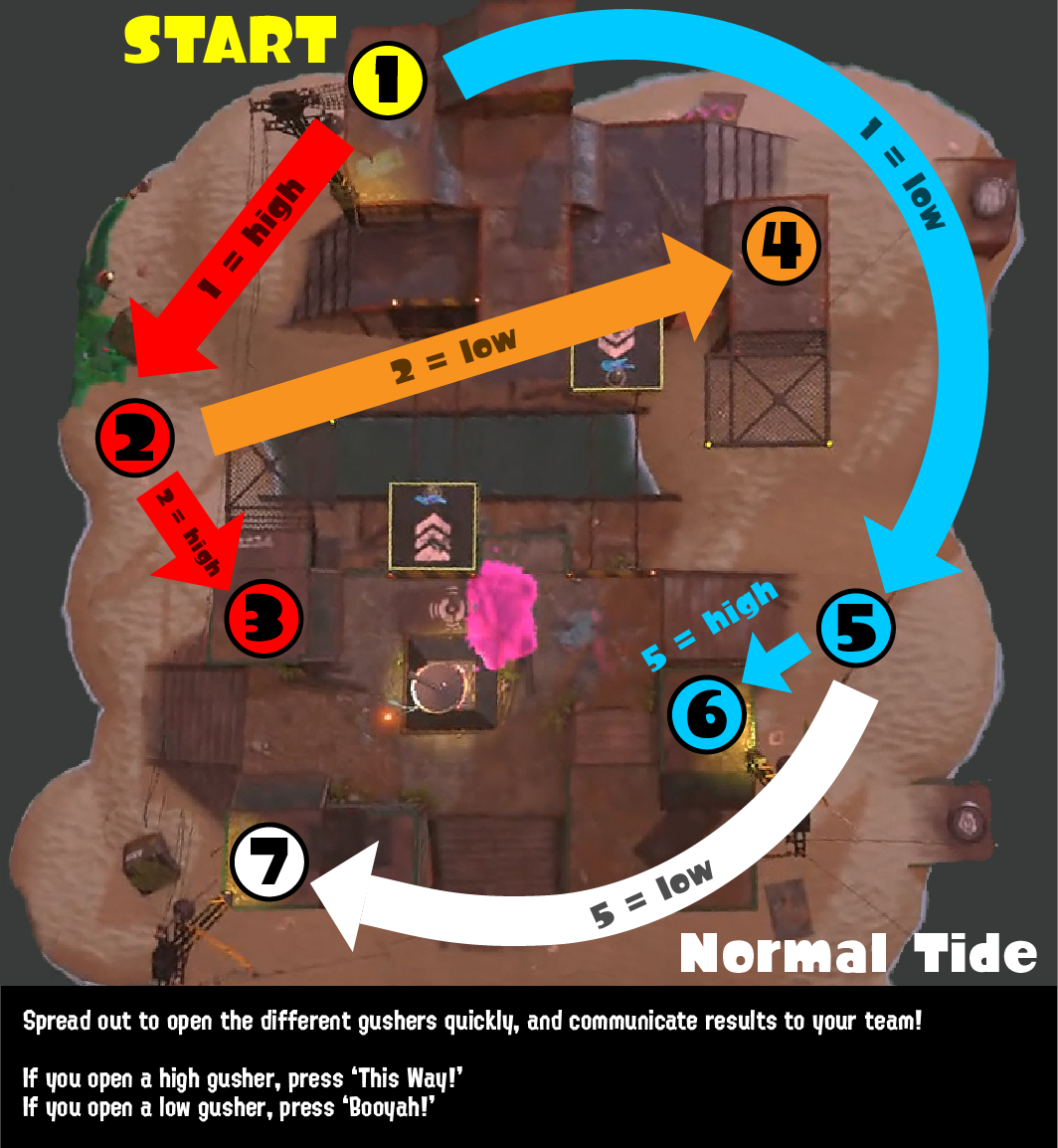

This is the commonly recommended strategy for Salmonid Smokeyard. Notice how, at each gusher, the strategy branches into two paths: one to take if the gusher is high, and another to take if the gusher is low.

If we redraw the gushers and the arrows connecting them, we can see the hierarchical nature of the strategy. The first gusher opened points to two “children”, which each point to two children of their own. This type of structure, in which each node can have other nodes as children, is called a tree. Since this tree describes the decisions we make depending on the result of opening each gusher, we can call it a decision tree.

Here’s another example of a decision tree, this time for Ark Polaris. Notice that some gushers only point to one child.

Some Notation

To make it easier to describe Goldie Seeking strategies without making fancy diagrams, we’ll use a standard notation to write a decision tree as a string of characters. The string G(H, L) represents a decision tree where G is the name of the gusher opened first, and H and L are the subtrees to follow depending on whether gusher G is high or low.

Here’s what the recommended Salmonid Smokeyard strategy looks like: f(d(b, g), e(c, a))

The advantage of this notation is that groups of adjacent gushers that all appear high when the Goldie hides in one of them will appear consecutively from left to right in the order that they should be opened. If a gusher is low, you skip to the next group in the string, just as you “skip” across the map to open a remote gusher.

What Makes a Strategy “Good”?

(WIP)

Part 2: The Problem, but With More Math

Now that we understand the math behind Goldie Seeking a little better, we can restate our initial question in a more exact form.

Let G be a graph whose vertices represent the gushers on a map and whose edges represent connections between gushers. To each vertex V, we assign a penalty value p(V) that describes how risky we think opening that gusher is. Our goal is to construct a valid decision tree T that minimizes the total cost of all gushers and therefore minimizes the expected cost in an average seeking round.

As mentioned before, the exact solution for a given graph will depend on how which decision trees we consider “valid” and how we calculate the cost of a gusher. We’ll start with simplified definitions, then gradually build up to the full version of the problem that the algorithm tries to solve.